News

The Guarani Kaiowá people’s tragedy (recounted by Brazilian magazine Epoca)

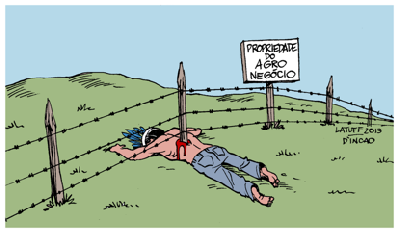

This work by Carlos Latuff, Brazilian press cartoonist, showing an indigenous man impaled on a stake – part of a “property of the agro-trade” fence – is enough to sum up the Guarani-Kaiowá people’s situation.

Epoca, a Brazilian magazine, recently shed light on the tragic fate of the Guarani Kaiowá people, and it feels like living through the darkest hours of the conquest of the Wild West all over again. The 21st century is far from being less cruel than its predecessors…

- Between 1915 and 1928, the Indian Protection Service (IPS), later replaced by the FUNAI, delimited eight small reserves in the south of the state, ignoring the community’s way of life. These areas were estimated to be sufficient to host the different Indian ethnic groups and family communities disseminated throughout the region. Together, the eight reserves amount to a mere 45,000 acres. Lucia Helena Rangel, an anthropology teacher at São Paulo Catholic Pontifical University, explains that “they mixed different communities, separated others from their sacred territories, the Tekohas (places to be born and to die in the Guarani culture). This caused and is still causing many conflicts between the Indians themselves”.

- Within these eight reserves, the IPS imposed military rules, created indigenous militias, supported evangelical missions and favored Indians of the Terena ethnic group during bundle distributions and in the institutional hierarchy, to the detriment of the Guarani Kaiowá,

- Rather than assimilating the Indians, the government decided to colonize the region, encouraging peasants from other states to migrate there by giving out numerous property deeds. This policy started after the Paraguayan War of the late 19th century, and intensified under the first Getúlio Vargas government (1930-1945). 75-acre lots were widely distributed. A large part of the agrarian reform was done on territories traditionally occupied by Indians.

- As opposed to what is happening in the north, where much of the land has been occupied, farmers from the Douro region have legitimate property deeds. This is the cornerstone of the farmers’ defense – even the fiercest indigenous cause activists cannot deny it. “The landowners have property deeds here, some of which are centuries old”, declared Eduardo Riedel, president of the Federação da Agricultura e Pecuaria do Mato Grosso do Sul (Famasul).

- All the Guarani Kaiowá have not been moved to one of the eight reserves. Many of them have stayed in the woods, living together with – and receiving favors from – small landowners. “Between the 1950s and the 1980s, during the farmers’ settlement, several Guarani Kaiowá worked on clearing the forests of the region they inhabited”, states anthropologist Tonico Benites, one of the few Guarani Kaiowá who had access to higher education, and who is currently preparing a PhD in Rio de Janeiro Federal University.

- Over the last two decades, everything has changed. With rampant deforestation, increasingly huge properties and mechanization, Indians still living in the forest have been repelled to the farms’ very limits, or forced to join one of the eight reserves, already overpopulated at the time.

- Anthropologists refer to a study giving an idea of the brutal transformation undergone by the region in recent decades. In the 1970s, in the city of Ponta Pora, bordering Paraguay, there were 450 active logging farms. Today, there are only two. The industry has nearly ceased to exist because there are no trees left to cut down. Anyone travelling in the region can witness the endless miles of soybean or sugarcane plantations, flat terrain only broken up by small chunks of forest (representing the legal minimum of 20% that all farms have to keep).

- Several families were afraid of going into the reserves, or refused to go too far from their usual areas, and started building camps on roadsides. These are the places where poverty is the most blatant.

- Others have decided to return to their traditional lands. Egon Heck, political specialist at the CIMI, explains that “those who cannot stand being confined on the highways’ embankments, or in an overpopulated reserve, try to reoccupy their Tekoha”. Those who try to get back to what little forest is left on farmland are treated as invaders by landowners. This is the case of the Laranjeira Nhanderu community, which, until recently, was camping in a ditch alongside BR-163. After two children died from malnutrition, two were run over by cars, and two committed suicide, the group, made of 100 Indians, crossed just about 1 kilometer of soy fields to get to the forest, where they are trying to settle down.

- facts & numbers -

Demography, location, density…

- Spread between Dourados and more than 20 neighboring municipalities, it is the largest indigenous population among the 220 known ethnic groups.

- 45,000 people live in the suburbs of medium-sized towns, in some soybean or sugarcane agricultural farms, alongside highways or in delimited areas which, together, amount to little more than 100,000 acres.

- If all Guarani Kaiowás were gathered in a single place, this indigenous town would have a population higher than that of Brazilian municipalities by 89% (source: Epoca Brazil)

Introducing the Guarani Kaiowá case

- In addition to the CIMI, the MPF and anthropologists, some international organizations such as the UN and Amnesty International have already denounced this people’s tragedy.

- The Guarani Kaiowá case is not unknown to Brazilian authorities. Shortly after she left the Ministry of the Environment, senator Marina Silva (PV-CA) wrote a letter to president Lula, warning him of the “worst humanitarian crisis” in this region. Just as adamant was the deputy general public prosecutor Deborah Duprat. She described the situation as “the greatest known tragedy in the indigenous question worldwide.”

Murdered, driven to commit suicide; Guarani Kaiowá, the slow genocide

- With the second largest autochthonous population in the country, Mato Grosso do Sul is the state with the highest rate of indigenous murders. For the past 8 years, 250 murders of indigenous people were committed in this state, compared to 202 in the rest of Brazil. Almost all of the victims were from the Guarani Kaiowá people.

- Between 2003 and 2010, 83% of suicides were committed by Guarani Kaiowás (176 cases, compared to 30 in the rest of Brazil). In this people’s recent history, suicides among children were reported, which is rare in any circumstances.

The Guarani Kaiowá life expectancy

- Even in war conditions, an Iraqi child will live 14 years longer than a Guarani Kaiowá child. A Haitian child will live 16 years longer.

- As for adults, life expectancy does not exceed 45 years, as is the case in Afghanistan, where Brazilians in general have a 73-year life expectancy.

- In 2005, malnutrition caused the death of many children. Since then, to hide this deficiency, the government has been distributing food stamps. According to the FUNAI, an estimate of 80% of the Guarani Kaiowá depend on food stamps to survive.

- Child mortality is 38 deaths for 1,000 births, compared to an average of 25 in the rest of Brazil.

© Epoca - translated by Mahault Thillaye

Date : 20/07/2015