News

Canadian oil company threatens the survival of Peru’s ‘Jaguar people’

Matses Tribe little girl.

Source : theecologist.org

The Peruvian Government is yet again failing to protect the rights of its Indigenous citizens, and if history is anything to go by it is no wonder that the Matses tribe fear for themselves and other nearby tribal peoples. Sarah Gilbertz reports.

The Yaquerana River in the Amazon rainforest marks the border between Peru and Brazil, but to the Matsés tribe, who live on both sides of it, this international border is meaningless. To them the streams, floodplains, and white-sand forests make up an ancestral territory that is shared by the entire tribe.

Today they are at risk of losing their land to a Canadian oil company which plans to cut hundreds of miles of seismic testing lines through their forest home and to drill exploratory wells.

There are around 2,200 Matsés living on the Peru-Brazil frontier in the Amazon rainforest. They hunt, fish and grow crops in their gardens; little is imported into their communities and most of what they need for survival comes from the rainforest. These communities live close to the riverbank, and every morning before the children go to school, they will join their parents and to catch the day’s fish.

The Matsés men hunt for animals such as tapir and paca – a large rodent – using bows and arrows, traps, and shotguns. To increase courage and hunting ability, the Matsés rely on the fluids of a green tree frog known as ‘acate’. Men collect the fluid by rubbing the frog’s skin with a stick, which is then applied to small holes burnt into the recipient’s skin. Dizziness and nausea soon give way to a feeling of clarity and strength that can last for several days. Another way of enhancing strength and energy is to blow tobacco, or ‘nënë’ snuff up each other’s nose.

When school is out, parents take their children to their gardens and teach them how to grow their own food. The Matsés grow a wide variety of crops, including staples such as plantain and manioc. Sweet plantains are used to make a drink called Chapo; women cook the ripened fruit and squeeze its soft flesh through homemade palm-leaf sieves. The drink is then served warm by the fire.

The Matsés depend almost entirely on their land and the forest for survival. “We don’t eat factory foods; we don’t buy things”, explains a member of the Matsés tribe to a researcher of the tribal rights organisation Survival International “that is why we need space to grow our own food”.

The ‘Jaguar people’

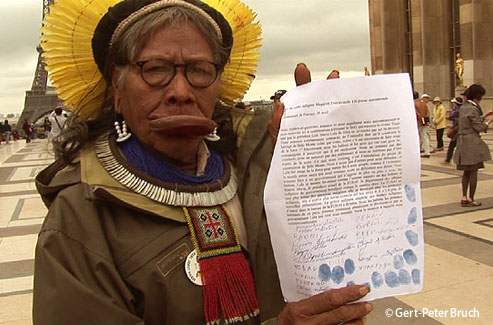

Together with the closely related Matis tribe, the Matsés have been known as the ‘Jaguar people’ for their facial decorations and tattoos, which resemble the jaguar’s whiskers and teeth.

The Matsés were first contacted in 1969 by members of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, a US missionary group. The missionaries arrived following violent clashes between local settlers attempting to build a road through the Matsés territory, and the Indians, who were defending their land. The colonists were threatening to kill the Matsés with bombs and poison gas thrown from planes. Violence escalated when several settlers occupied one of the Matsés’ communal houses and raised the Peruvian flag.

The Matsés have preserved much of their unique traditional medicine and knowledge of medicinal plants. The healers have a deep understanding of forest plants and how they can be used to cure illness. To the Matsés, plants and animals have spirits just as humans do, and can ail or heal a human body. The healer will identify the cause of the patient’s illness and treat it with its respective plant medicine. But since contact, the Matsés have suffered severe illness, especially malaria and introduced diseases that their plant-based medicines cannot cure.

Threat from Canadian oil company

In 2012, the Canadian oil company Pacific Rubiales began to explore for oil on part of the Matsés’ ancestral land. The $36 million project will see hundreds of seismic lines cut through 700 sq km of forest, and wells drilled in search of oil, affecting the headwaters of three major rivers that are essential to the Matsés’ livelihoods.

The Matsés are worried about the future of their forest and their own survival. In a rare interview with Survival International, Antonina Duni Goya Nesho, a Matsés woman, said “Oil will destroy the place where our rivers are born. What will happen to the fish? What will the animals drink?”

Although the Matsés have repeatedly opposed the company’s work on their land, their protests have been ignored. In March 2013, hundreds of Matsés Indians from Peru and Brazil gathered on the border and called on their government to stop the exploration, warning that the work will devastate their forest home. “Go and tell the whole world that the Matsés are firm in our position against the oil company” said one Matsés man; “We do not want it invading our land!”

Uncontacted Indians

The Matsés are not only concerned about their own tribe’s future; they also worry about the uncontacted people living close to them in both Peru and Brazil. Uncontacted tribes are peoples who have no peaceful contact with mainstream society. Today there are an estimated 100 uncontacted tribes in the world.

Those in the Amazon carry a tragic legacy: often they are descendants of the survivors of the rubber boom which swept through the Amazon at the turn of the 20th century. Thousands of rubber tappers flooded into the most isolated corners of the Amazon, home to tens of thousands of Amazon Indians, enslaving the Indians and bringing diseases to which they had no immunity. Within a few years, 90% of the Indian population had been killed, or died from mistreatment or epidemics. This history is seared into the collective memory of the survivors, and as a consequence, some avoid contact with the outside at all costs.

Even in more recent times, epidemics of disease have devastated recently-contacted people. In Peru, more than 50% of the previously-uncontacted Nahua tribe were wiped out following oil exploration on their land in the early 1980s, and the same tragedy engulfed the Murunahua in the mid-1990s after being forcibly contacted by illegal mahogany loggers.

“The uncontacted people move from place to place, and when they see a white person they flee”, says a Matsés man; “when they hear someone coming close they hide their tracks with leaves and sticks; but I know they are there; I can assure you that they are there”.

During the 1990s, when loggers flooded into Matsés territory, the uncontacted Indians fled the region. But the Matsés said that the isolated people have been returning. They are now afraid that the oil company will force them to flee once again.

The Canadian oil company’s gas block ‘135’ lies directly over an area that has been proposed as a reserve to protect the uncontacted tribes on the Peruvian side, but the effects of the oil work are also likely to be felt across the border in Brazil’s Javari Valley, home to several other uncontacted tribes.

How to help the Matsés

Despite promising to protect the rights of its Indigenous citizens, the Peruvian Government has allowed Pacific Rubiales to go ahead with its project, in violation of international law.

“We sent letters to the Government rejecting the oil company but we received no reply”, said Antonina Duni Goya Nesho. “This is our land; this is where we are from. Our leaders have fought with the Government many times, but they must be deaf or they just don't respect us”.

To help the Matsés in protecting their land and their future send an e-mail to Pacific Rubiales’ President via Survival International’s website, telling him to pull out of the Matsés’ territory before their lives are destroyed forever. You can also write a letter to the Peruvian President, S. E. Ollanta Humala urging him to cancel Pacific Rubiales’ contracts.

Sarah Gilbertz is press assistant for Survival International.

© theecologist.org : original article

Date : 13/05/2013