News

Peru's Pakitzapango Mega-Dam: Wild Rivers and Indigenous Peoples at Risk

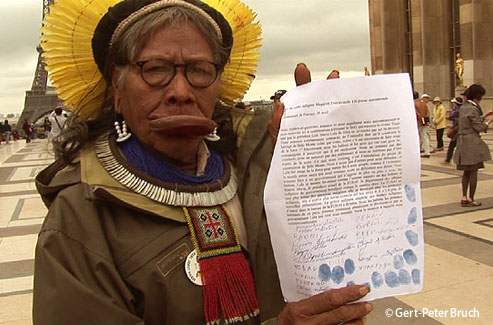

In the Ashaninka community

Source : Rainforest fondation UK

The Peruvian Amazon is a treasure trove of biodiversity. Its aquatic ecosystems sustain bountiful fisheries, diverse wildlife, and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of people. White-water rivers flowing from the Andes provide rich sediments and nutrients to the Amazon mainstream.

But this naturally wealthy landscape faces an ominous threat. Brazil's emergence as a regional powerhouse has been accompanied by an expansionist energy policy and it is looking to its neighbours to help fuel its growth. The Brazilian government plans to build more than 60 dams in the Brazilian, Peruvian and Bolivian Amazon over the next two decades. These dams would destroy huge areas of rainforest through direct flooding and by opening up remote forest areas to logging, cattle ranching, mining, land speculation, poaching and plantations. Many of the planned dams will infringe on national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and some of the largest remaining wilderness areas in the Amazon Basin. By changing the natural cycles of the region's river systems - the lifeblood of the Amazon rainforest - large dams threaten the rainforest and the web of life it supports.

Brazil's Role in Peru's Amazon Dams

In June 2010, the Brazilian and Peruvian governments signed an energy agreement that opens the door for Brazilian companies to build a series of large dams in the Peruvian Amazon. The energy produced is largely intended for export to Brazil. The first five dams - Inambari, Pakitzapango, Tambo 40, Tambo 60 and Mainique - would cost around US billion, and financing is anticipated to come from the Brazilian National Development Bank (BNDES). The Peruvian government is hoping that the dams will boost foreign exchange earnings from energy exports, increase tax revenue, and help build local economies through the services and jobs required during dam construction. In a rush to facilitate private investment, the government is pushing through two laws that would expedite approvals of dams, pipelines and road projects, and exempt them from obtaining environmental certifications as a prerequisite for concession approval. The electricity inter-connection between Brazil and Peru is part of a broader energy integration scheme in Latin America. The dams would enable the integration of Brazil with the national systems of the Andean region, and in turn the Brazilian connection would link Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay to the rest of South America. Brazilian electric utility Eletrobras is leading the evaluation of the projects' feasibility in cooperation with Brazilian private companies such as Engevix, OAS, Andrade Gutierrez and Odebrecht.

Ashaninka Reject Pakitzapango Dam

One of the first projects in line to be built is the Pakitzapango Dam, which would wall off the Ene River with a 165-metre-high dam. The project is being developed by Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht and electric utility Eletrobras, which estimate that it will generate 2,000 megawatts (MW) mostly for export to Brazil. In addition to the Pakitzapango Dam, the Tambo 40,Tambo 60 and Sumabeni dams are also planned in the Ene-Tambo River Basin. Ten Ashaninka communities with close to 10,000 people living on both sides of the Ene River would be displaced and their livelihoods harmed by Pakitzapango alone. The health of the Ene River is crucial for the Ashaninka indigenous people, who depend on its fish resources, the fertile soils of its floodplains, and the many foods and products in the surrounding forests. They also cultivate small plots of land on which they grow manioc, yams, peanuts, bananas and pineapples. The forest provides edible and medicinal roots, honey, and materials to make baskets and mats. Yet the reservoir would flood 734 square kilometres of forests, arable lands and water sources upon which the Ashaninka depend.

Even though Peru ratified Convention No. 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO), which requires that indigenous and tribal peoples be consulted on issues that affect them, the Ashaninka people whose lands are legally protected have not been consulted about the Pakitzapango Dam. The Ashaninka are one of the largest indigenous groups in the Peruvian Amazon, numbering close to 70,000. Although the Spaniards never conquered the Ashaninkas, the intrusion on their lands - first by rubber-tappers and missionaries, and later by settlers, guerrillas, coca growers and traffickers - brought about enslavement, torture, displacement and massacres. During the internal war in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, the Maoist guerrilla group Shining Path gained control over areas of the Ene and Upper Tambo rivers. Many Ashaninka were forcibly displaced or enslaved, and close to 6,000 were killed. Thirty to forty communities disappeared. Yet, the resiliency of the Ashaninka is extraordinary, and they maintain their ethnic identity. Today, they are fighting against illegal logging and coca growing, and are working on managing and protecting their forests. The Ashaninka Organization of the Rio Ene (CARE), initially created in 1993 to support the Ashaninkas after the war, is the leading Ashaninka organization working in defense of communities, forests, and lands, and to protect the Ene River.

Pakitzapango Energia, S.A.C. obtained a temporary concession to conduct feasibility studies for the project in 2008. To counter this, CARE presented a legal administrative action against the project before the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM) in 2010. MINEM established that the feasibility studies were not concluded within the time allowed, and resolved not to renew the temporary concession to Pakitzapango Energia. MINEM's decision has been appealed, and the case may end up in the Constitutional Court. Stopping construction of the Pakitzapango Dam and others planned for the Ene-Tambo River Basin is crucial for the survival of the Ashaninka as a people.

© Rainforest Fondation UK / www.rainforestfoundationuk.org

Date : 08/09/2012