News

BELO MONTE : The Beautiful and the Dammed - part 1/2

Illustration by Andrew Holder

Source : www.myoo.com

Rachel Riederer puts a spotlight on the individuals fighting back against a massive dam that would turn their homes into a lost city of Atlantis

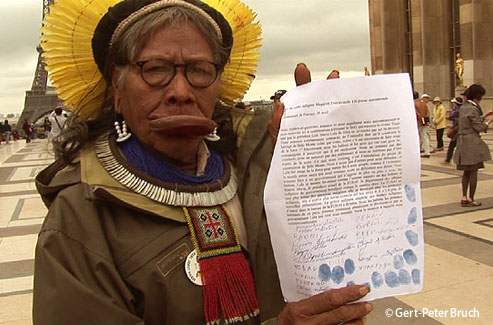

On Wednesday, October 26th of this year Sheyla Juruna, a leader of the Juruna people, an indigenous Amazonian tribe, held a small press conference in the Washington, D.C. drizzle. In a city of suits, Sheyla Juruna stood out in her leggings, flip-flops, and feather headband, her legs painted with traditional wave designs representing the Jurunas’ connection to their river, a major tributary of the Amazon.

She was standing outside the office of the Organization of American States because she had just been stood up by the government of Brazil.

The Juruna are one of several groups on the Xingu (pronounced SHING-oo) River that would be affected by the massive Belo Monte, or Beautiful Mountain, dam set within the state of Pará in northern Brazil, a region whose untamed jungles and distance from the industrial south have earned in the nickname “Brazil’s Wild West.” If completed, the dam’s reservoir will flood over 650 square kilometers of land and lead to the displacement of more than 20,000 indigenous people. The project will also divert nearly all the flow of a 60-mile stretch of the Xingu called the Big Bend, radically changing the traditional way of life of the Juruna and neighboring tribes, who depend on the river, and its network of tributaries. The Xingu is so broad and branching that photos of local towns seem like they’re on islands rather than riverbanks. Sheyla has called Belo Monte “a project of death,” saying that it will destroy her people’s way of life. When I asked her what all the Juruna use the river for, she said simply: “everything.”

Sheyla Juruna had made the two-day journey from her village of Boa Vista for a meeting at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The IACHR was to mediate the dispute between indigenous groups and the Brazilian government, and had requested that Brazil suspend licensing and construction of the dam until it had consulted with local tribes. Brazil ignored both requests; it recently granted the developers full licensing, and declined to attend the meeting, the first time that the Brazilian government has ever opted out of such a meeting with the IACHR.

Brazil’s 1988 constitution protects indigenous groups—there’s even a law against entering the rainforest lands where the last uncontacted tribes live—and developers are required to get consent from any indigenous communities whose land will be affected by new projects before beginning construction. But the definition of consent has been a sticking point. The tribes of the Xingu say they were informed of the project but not given the opportunity to say yes or no. “There’s a huge gap between discourse and practice,” said Andressa Caldras, Executive Director of Global Justice. “The response of the Brazilian government was arrogant and anti-democratic. It hearkens back to the days of the military dictatorship,” comparing the current government to the authoritarian regimes that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985. During those years the Brazilian executive branch was a revolving door for several repressive military leaders who squashed political opposition and bolstered the country’s economy with infrastructure projects of pharoahic proportions.

The debate is passionate on both sides. Brazil is not facing a power shortage, but will need additional power sources for continued economic growth. And in some ways, Belo Monte seems perfect. One reverent engineer is quoted as saying, “God only makes a place like Belo Monte once in a while—this place was made for a dam.” The Big Bend runs quickly downhill, and developers see the broad, flat basin inside the Big Bend’s curve as a natural reservoir; these are some of the qualities that make a good dam site. Atossa Soltani, the Executive Director of the NGO Amazon Watch, also finds the place beautiful, but for a different reason. She thinks of the Amazon, with its crucial role in the Earth’s water, heat, and weather cycling as “the heart of the planet.” And a dam at Belo Monte? “It may be an engineer’s wet dream,” she told me, “but it should be everyone else’s nightmare.”

Soltani has seen the ecological and social disruption that follows big dams. The 600+ square kilometers that will be flooded are just the first wave of deforestation. The 90,000-person town of Altamira, near the proposed site, expects to receive an influx of 100,000 people seeking construction and industrial jobs. The construction of access roads, and a huge spike in population in local towns, will result in nearly ten times more forestland being cleared. And resettlement often spells the end of indigenous life. Soltani has visited villages in Amazonia where people are eating canned tunafish on the banks of the world’s mightiest river. “We’ve seen this happen. You can go and visit the Tucuruí dam, one river basin over from Belo Monte. About 20,000 people were resettled into a mosquito swamp where they couldn’t live. They’re promised a new life, new land, but these things don’t materialize. Kids move to cities, you have high levels of alcoholism, abuse, and prostitution. Within a few generations you have loss of language, just total disintegration.” The groups on the Xingu have seen the upheaval that comes from resettlement and don’t want the decisions about their future to be made by strangers in Brasilia.

Kayapó leader Raoni Metuktire has said that if this dam goes forward, “there will be a war so that white men cannot interfere on our lands again.” I asked Soltani, who has been working with indigenous groups in the Amazon for more than 15 years, what she thought about this. “The Kayapo have a reputation for being warriors. They are fierce, and when they don’t like something they organize against it and they stop it.” The warfare the Kayapo are talking about is civil disobedience, more Occupy Wall Street than Battle of Little Bighorn. “They are physically preparing to put themselves in the path of the project, to stop the dam. And obviously it’s going to be an important thing for the media to bear witness to, otherwise the military can just come in and engage in violent reprisal.” Soltani’s fear makes sense in the current tense climate in the region; eight environmentalists in the Amazon have been killed this year.

Still, the Kayapó have reason to hope for success. In 1989, the dam on the Xingu was almost built (under a different name, the Kararaô, and with a slightly different layout). Local tribespeople, including the Juruna’s neighbors the Kayapó and Arara, staged a well-attended rally in the nearby town of Altamira, drawing international media attention. Opposition was so strong that the developers had to drop the project.

The people of the Xingu are hoping them can replicate those results. On October 27, the day after Juruna’s quiet press conference in front of the OAS, four hundred representatives from indigenous groups and other riverine communities occupied the Belo Monte construction site and blocked the Trans-Amazon highway. They stayed for 15 hours, disbursing when two government officials and several lawyers from the dam-building consortium arrived with an injunction. That injunction is not the end of the road, though. There are 14 court cases underway in various Brazilian courts that challenge the dam.

It can be hard to imagine exactly what the loss of a river does to a culture like the Juruna. Understanding the role of the Xingu in the lives of canoe people like the Juruna and Kayapó requires a shift in perspective. “Of course every human being depends on water for life,” Sheyla Juruna told me. “But our connection to the river is not just day-to-day. It is our life, the source of all our spirituality.” The Xingu is their food source and water source, but it is also workplace, transportation, and church. Curtailing the flow of the Big Bend would affect them the way that shutting down subway lines, cell phone towers, water supply, internet service, and bodegas would affect a major city. When Hurricane Irene threatened to do precisely that earlier this year to New York, people stockpiled bottled water and batteries, and hunkered down. It was just going to be a few days, and there was nothing else to do: you can’t stop a hurricane. You might, though, be able to stop a dam.

Rachel Riederer, is an essayist and environmental journalist

© Myoo - Rachel Riederer

http://myoo.com/stories/the-beautiful-and-the-dammed/

Date : 25/11/2011